Which Of The Following Behaviors Would A Person With Low Self-control Not Be Likely To Exhibit?

Chapter three. The Self

The Feeling Self: Self-Esteem

- Define cocky-esteem and explain how it is measured by social psychologists.

- Explore findings indicating diverseness in cocky-esteem in relation to culture, gender, and historic period.

- Provide examples of ways that people attempt to increase and maintain their self-esteem.

- Outline the benefits of having high cocky-esteem.

- Review the limits of self-esteem, with a focus on the negative aspects of narcissism.

As we have noted in our discussions of the self-concept, our sense of cocky is partly determined by our noesis. Withal, our view of ourselves is besides the product of our touch, in other words how we experience almost ourselves. Just every bit we explored in Chapter ii, cognition and affect are inextricably linked. For example, self-discrepancy theory highlights how we feel distress when we perceive a gap between our actual and ideal selves. We will now examine this feeling self, starting with perhaps its nigh heavily researched aspect, self-esteem.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to the positive (loftier self-esteem) or negative (low self-esteem) feelings that we accept about ourselves. We experience the positive feelings of high cocky-esteem when we believe that we are good and worthy and that others view united states of america positively. We experience the negative feelings of low self-esteem when nosotros believe that we are inadequate and less worthy than others.

Our self-esteem is determined by many factors, including how well we view our own performance and appearance, and how satisfied we are with our relationships with other people (Tafarodi & Swann, 1995). Self-esteem is in part a trait that is stable over time, with some people having relatively high self-esteem and others having lower self-esteem. But self-esteem is also a state that varies day to day and even hour to hr. When we accept succeeded at an important chore, when we have washed something that we think is useful or important, or when we experience that we are accustomed and valued past others, our self-concept volition contain many positive thoughts and we will therefore take high self-esteem. When we have failed, done something harmful, or feel that we have been ignored or criticized, the negative aspects of the self-concept are more accessible and we experience low self-esteem.

Cocky-esteem can exist measured using both explicit and implicit measures, and both approaches find that almost people tend to view themselves positively. I mutual explicit self-report measure of self-esteem is the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Figure 3.8). Higher scores on the scale indicate college self-esteem.

Figure 3.8 The Rosenberg Cocky-Esteem Scale

Delight rate yourself on the following items by writing a number in the blank earlier each statement, where you

1 = Strongly Disagree ii = Disagree 3 = Agree 4 = Strongly Agree

- _____I feel that I'thou a person of worth, at least on any equal base with others.

- _____I feel that I have a number of good qualities.

- _____All in all, I am inclined to think that I am a failure (R).

- _____I am able to practice things likewise as other people.

- _____I feel I practise non have much to be proud of. (R)

- _____I have a positive mental attitude towards myself.

- _____On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.

- _____I wish I could accept more respect for myself. (R)

- _____I certainly feel useless at times. (R)

- _____At times I retrieve I am no good at all. (R)

Note. (R) denotes an item that should exist reverse scored. Subtract your response on these items from v before calculating the total. Data are from Rosenberg (1965). Society and the adolescent cocky-paradigm. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Numerous studies have used the Rosenberg scale to assess people'due south self-esteem in many areas of the world. An interesting finding in many samples from the Western earth, particularly in North America, is that the average score is oft significantly higher than the mid-point. Heine and Lehman (1999), for example, reported meta-analytic information indicating that less than 7% of participants scored below the mid-betoken! One interesting implication of this is that participants in such samples classified as having low self-esteem on the basis of a median split will typically actually have at least moderate cocky-esteem.

If so many people, particularly in individualistic cultures, report having relatively loftier cocky-esteem, an interesting question is why this might exist. Perchance some cultures place more importance on developing high self-esteem than others, and people correspondingly feel more pressure to report feeling skillful nearly themselves (Held, 2002). A problem with measures such as the Rosenberg scale is that they can be influenced past the want to portray the cocky positively. The observed scores on the Rosenberg scale may be somewhat inflated because people naturally try to make themselves look as if they have very high self-esteem—possibly they lie a bit to the experimenters to make themselves wait amend than they actually are and mayhap to brand themselves feel better. If this the case, so nosotros might expect to find boilerplate levels of reported self-esteem to be lower in cultures where having high self-worth is less of a priority. This is indeed what has generally been plant. Heine and Lehman (1999) reported that Japanese participants living in Nihon showed, on average, moderate levels of self-esteem, normally distributed around the scale mid-point. Many other studies have shown that people in Eastern, collectivistic cultures report significantly lower self-esteem than those from more Western, individualistic ones (Campbell et al., 1996). Do, then, such differences reflect these unlike cultural priorities and pressures, or could it be that they reflect genuine differences in actual self-esteem levels? There are no easy answers here, of course, but at that place are some findings from studies, using different methods of measuring cocky-esteem, that may shed some light on this issue.

Indirect measures of self-esteem have been created—measures that may provide a more accurate picture of the self-concept because they are less influenced by the desire to make a positive impression. Anthony Greenwald and Shelly Farnham (2000) used the Implicit Association Test to written report the self-concept indirectly. Participants worked at a calculator and were presented with a series of words, each of which they were to categorize in ane of two means. I categorization decision involved whether the words were related to the cocky (e.g., me, myself, mine) or to some other person (e.k., other, them, their). A second categorization conclusion involved determining whether words were pleasant (east.g., joy, grinning, pleasant) or unpleasant (due east.g., pain, death, tragedy). On some trials, the self words were paired with the pleasant items, and the other words with the unpleasant items. On other trials, the cocky words were paired with the unpleasant items, and the other words with the pleasant items. Greenwald and Farnham constitute that on boilerplate, participants were significantly faster at categorizing positive words that were presented with self words than they were at categorizing negative words that were presented with self words, suggesting, again, that people did have positive self-esteem. Furthermore, there were likewise meaningful differences among people in the speed of responding, suggesting that the measure captured some individual variation in implicit self-esteem.

A number of studies accept since explored cross-cultural differences in implicit self-esteem and take not found the same differences observed on explicit measures like the Rosenberg scale (Yamaguchi et al., 2007). Does this mean that nosotros can conclude that the lower scores on self-report measures observed in members of collectivistic cultures are more credible than real? Maybe not only yet, especially given that the correlations between explicit and implicit measures of cocky-esteem are oftentimes quite pocket-sized (Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999). Nevertheless, values such equally modesty may be less prioritized in individualistic cultures than in collectivistic ones, which may in plough reverberate differences in reported cocky-esteem levels. Indeed, Cai and colleagues (2007) plant that differences in explicit self-esteem between Chinese and American participants were explained past cultural differences in modesty.

Another interesting aspect of diversity and self-esteem is the average difference observed between men and women. Across many countries, women have been constitute to report lower self-esteem than men (Sprecher, Brooks, & Avogo, 2013). However, these differences take more often than not been plant to exist modest, particularly in nations where gender equality in police and opportunity is higher (Kling, Hyde, Showers, & Buswell, 1999). These findings are consistent with Mead'due south (1934) suggestion that self-esteem in role relates to the view that others accept of our importance in the wider world. As women's opportunities to participate in careers outside of the dwelling house have increased in many nations, so the differences between their cocky-esteem and that of men have decreased.

There are also some interesting age differences in self-esteem that have been uncovered. In a large Internet survey, Robins, Trzesniewski, Tracy, Gosling, & Potter (2002) found that cocky-esteem tends to decrease from childhood to early adolescence, and then rises steadily from adolescence into adulthood, ordinarily until people are well into their sixties, afterward which point it begins to reject. One interesting implication of this is that nosotros often will accept higher self-esteem later in life than in our early adulthood years, which would appear to run confronting ageist stereotypes that older adults accept lower self-worth. What factors might help to explain these age-related increases in cocky-esteem? 1 possibility relates dorsum to our give-and-take of cocky-discrepancy theory in the previous section on the cognitive self. Call back that this theory states that when our perceived self-discrepancy between our current and ideal selves is minor, we tend to feel more positive about ourselves than when we see the gap as being large. Could it exist that older adults have a electric current view of self that is closer to their ideal than younger adults, and that this is why their self-esteem is ofttimes college? Evidence from Ryff (1991) suggests that this may well be the case. In this study, elderly adults rated their electric current and ideal selves as more similar than either center-anile or young adults. In part, older adults are able to more than closely marshal these 2 selves because they are better able to realistically adjust their platonic standards as they age (Rothermund & Brandstadter, 2003) and considering they engage in more than favorable and age-appropriate social comparisons than do younger adults (Helgeson & Mickelson, 2000).

Maintaining and Enhancing Self-Esteem

Equally nosotros saw in our earlier discussion of cultural differences in self-esteem, in at to the lowest degree some cultures, individuals appear motivated to report high self-esteem. Every bit we shall now see, they too oftentimes actively seek out higher cocky-worth. The extent to which this is a universal cultural pursuit continues to be debated, with some researchers arguing that it is establish everywhere (Brown, 2010), while others question whether the need for positive cocky-regard is as valued in all cultures (Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999).

For those of us who are actively seeking higher self-esteem, one manner is to be successful at what nosotros do. When nosotros get a skilful form on a test, perform well in a sports match, or get a date with someone nosotros actually like, our self-esteem naturally rises. I reason that many of the states accept positive self-esteem is because we are generally successful at creating positive lives. When nosotros fail in i domain, we tend to move on until nosotros find something that we are skillful at. We don't always expect to get the best course on every exam or to be the best player on the team. Therefore, we are often not surprised or hurt when those things don't happen. In brusque, we feel good nigh ourselves because we do a pretty skilful job at creating decent lives.

Another manner we tin can boost our self-esteem is through building connections with others. Forming and maintaining satisfying relationships helps u.s.a. to feel skilful almost ourselves. A mutual way of doing this for many people around the world is through social networking sites. There are a growing number of studies exploring how nosotros do this online and the effects that it has on our self-worth. One common way on Facebook is to share status updates, which we hope that our friends will then "similar" or comment on. When our friends do not respond to our updates, however, this tin negatively impact how we feel about ourselves. I written report found that when regular Facebook users were assigned to an experimental condition where they were banned from sharing information on Facebook for 48 hours, they reported significantly lower levels of belonging and meaningful existence. In a 2nd experiment, participants were allowed to post material to Facebook, but half of the participants' profiles were fix upward by the researchers non to receive any responses, whether "likes" or comments, to their status updates. In line with predictions, that group reported lower self-esteem, level of belonging, level of control, and meaningful being than the control grouping who did receive feedback (Tobin, Vanman, Verreynne, & Saeri, 2014). Whether online or offline, then, feeling ignored by our friends tin dent our cocky-worth. We will explore other social influences on our self-esteem afterward in this affiliate.

Research Focus

Processing Information to Enhance the Self

Although we can all exist quite good at creating positive self-esteem past doing positive things, it turns out that nosotros often practice not cease at that place. The desire to encounter ourselves positively is sometimes strong enough that it leads united states to seek out, process, and remember information in a way that allows us to see ourselves even more positively.

Sanitioso, Kunda, and Fong (1990) had students read almost a report that they were told had been conducted by psychologists at Stanford University (the study was actually fictitious). The students were randomly assigned to two groups: one grouping read that the results of the research had showed that extroverts did better than introverts in bookish or professional settings after graduating from college; the other group read that introverts did improve than extroverts on the same dimensions. The students then wrote explanations for why this might be true.

The experimenter so thanked the participants and led them to another room, where a second study was to be conducted (you volition have guessed already that although the participants did not remember so, the two experiments were actually part of the same experiment). In the 2nd experiment, participants were given a questionnaire that supposedly was investigating what different personality dimensions meant to people in terms of their own experience and beliefs. The students were asked to list behaviors that they had performed in the past that related to the dimension of "shy" versus "outgoing"—a dimension that is very close in pregnant to the introversion-extroversion dimension that they had read about in the first experiment.

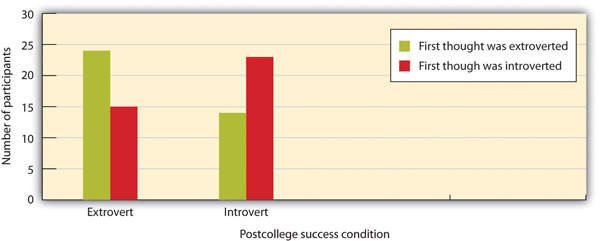

Effigy 3.ix, "Enhancing the Self," shows the number of students in each status who listed an extroverted behavior first, and the number who listed an introverted behavior first. Y'all tin can run into that the showtime memory listed by participants in both conditions tended to reflect the dimension that they had read was related to success according to the inquiry presented in the start experiment. In fact, 62% of the students who had just learned that extroversion was related to success listed a memory nigh an extroverted behavior first, whereas only 38% of the students who had but learned that introversion was related to success listed an extroverted beliefs first.

Sanitioso, Kunda, and Fong (1990) institute that students who had learned that extroverts did better than introverts subsequently graduating from college tended to list extroverted memories about themselves, whereas those who learned that introverts did meliorate than extroverts tended to listing introverted memories.

Information technology appears that the participants drew from their memories those instances of their ain behavior that reflected the trait that had the most positive implications for their self-esteem—either introversion or extroversion, depending on experimental condition. The desire for positive cocky-esteem made events that were consequent with a positive self-perception more than accessible, and thus they were listed first on the questionnaire.

Other research has confirmed this full general principle—people frequently endeavor to create positive self-esteem whenever possible, fifty-fifty it if involves distorting reality. We tend to take credit for our successes, and to blame our failures on others. We think more of our positive experiences and fewer of our negative ones. As we saw in the discussion of the optimistic bias in the previous affiliate near social noesis, nosotros approximate our likelihood of success and happiness as greater than our likelihood of failure and unhappiness. We recollect that our humor and our honesty are above average, and that we are ameliorate drivers and less prejudiced than others. We as well distort (in a positive way, of class) our memories of our grades, our performances on exams, and our romantic experiences. And we believe that nosotros can control the events that we will experience to a greater extent than we really can (Crocker & Park, 2004).

Once over again, though, there are some important cultural differences to note with people in individualistic cultures pursuing these cocky-enhancing strategies more than vigorously and more oftentimes than those from more collectivistic backgrounds. Indeed, in a large-scale review of studies on self-enhancement, Heine (2004) concluded that these tactics are not typically used in cultures that value interdependence over dependence. In cultures where high self-esteem is not equally socially valued, people presumably do non experience the same demand to distort their social realities to serve their self-worth.

There is also considerable personal multifariousness in the tendency to use self-enhancement. Stable differences between individuals have been uncovered in many studies across a range of cocky-enhancing strategies (Hepper, Gramzow, & Sedikides, 2010; John & Robins, 1994; Kwan, John, Kenny, Bond, & Robins, 2004).

Narcissism and the Limits of Self-Enhancement

Our discussion to this point suggests that many people will generally try to view themselves in a positive light. We emphasize our positive characteristics, and we may fifty-fifty in some cases distort information—all to help us maintain positive cocky-esteem. There can be negative aspects to having too much self-esteem, nonetheless, specially if that esteem is unrealistic and undeserved. Narcissism is a personality trait characterized by overly loftier self-esteem, self-admiration, and cocky-centeredness. Narcissists tend to concur with statements such as the following:

- "I know that I am good because everybody keeps telling me so."

- "I tin normally talk my way out of anything."

- "I like to be the center of attention."

- "I have a natural talent for influencing people."

Narcissists can be perceived every bit mannerly at first, but often alienate others in the long run (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003). They can as well make bad romantic partners as they often behave selfishly and are e'er set up to wait for someone else who they retrieve will be a amend mate, and they are more likely to exist unfaithful than non-narcissists (Campbell & Foster, 2002; Campbell, Rudich, & Sedikides, 2002). Narcissists are as well more likely to bully others, and they may respond very negatively to criticism (Baumeister et al., 2003). People who take narcissistic tendencies more often pursue self-serving behaviors, to the detriment of the people and communities surrounding them (Campbell, Bush, Brunell, & Shelton, 2005). Possibly surprisingly, narcissists seem to understand these things about themselves, although they appoint in the behaviors anyway (Carlson, Vazire, & Oltmanns, 2011).

Interestingly, scores on measures of narcissistic personality traits accept been creeping steadily upwards in recent decades in some cultures (Twenge, Konrath, Foster, Campbell, & Bushman, 2008). Given the social costs of these traits, this is troubling news. What reasons might there be for these trends? Twenge and Campbell (2009) argue that several interlocking factors are at work here, namely increasingly kid-centered parenting styles, the cult of celebrity, the office of social media in promoting self-enhancement, and the wider availability of piece of cake credit, which, they fence, has lead to more than people being able to larn status-related goods, in plow further fueling a sense of entitlement. Equally narcissism is partly about having an excess of self-esteem, it should by now come as no surprise that narcissistic traits are higher, on average, in people from individualistic versus collectivistic cultures (Twenge et al., 2008).

The negative outcomes of narcissism enhance the interesting possibility that loftier cocky-esteem in full general may not always be advantageous to us or to the people around us. One complication to the issue is that explicit self-report measures of cocky-esteem, like the Rosenberg scale, are not able to distinguish between people whose high self-esteem is realistic and appropriate and those whose self-esteem may be more inflated, even narcissistic (Baumeister et al., 2003). Implicit measures also do not provide a articulate picture, only indications are that more narcissistic people score higher on implicit self-esteem in relation to some traits, including those relating to social condition, and lower on others relating to relationships (Campbell, Bosson, Goheen, Lakey, & Kernis, 2007). A cardinal bespeak is that it can be difficult to disentangle what the effects of realistic versus unrealistic high cocky-esteem may be. Notwithstanding, it is to this thorny effect that we will now turn.

Social Psychology in the Public Interest

Does High Self-Esteem Cause Happiness or Other Positive Outcomes?

Teachers, parents, school counselors, and people in many cultures frequently assume that high self-esteem causes many positive outcomes for people who have it and therefore that we should try to increase it in ourselves and others. Possibly you agree with the idea that if you could increase your self-esteem, you lot would experience improve nigh yourself and therefore exist able to work at a higher level, or attract a more than desirable mate. If yous do believe that, you lot would not be alone. Baumeister and colleagues (2003) describe the origins and momentum of what they telephone call the cocky-esteem motility, which has grown in influence in various countries since the 1970s. For example, in 1986, the state of California funded a task strength nether the premise that raising self-esteem would help solve many of the land'southward problems, including criminal offense, teen pregnancy, drug abuse, school underachievement, and pollution.

Baumeister and colleagues (2003) conducted an extensive review of the research literature to decide whether having loftier self-esteem was as helpful every bit many people seem to recall it is. They began past assessing which variables were correlated with high self-esteem and then considered the extent to which high self-esteem acquired these outcomes. They establish that loftier self-esteem does correlate with many positive outcomes. People with high self-esteem get better grades, are less depressed, feel less stress, and may even live longer than those who view themselves more than negatively. The researchers besides found that high self-esteem is correlated with greater initiative and action; people with high self-esteem just practise more things. They are also more more than likely to defend victims confronting bullies compared with people with low self-esteem, and they are more probable to initiate relationships and to speak upward in groups. Loftier self-esteem people as well work harder in response to initial failure and are more willing to switch to a new line of try if the nowadays one seems unpromising. Thus, having high self-esteem seems to exist a valuable resource—people with high self-esteem are happier, more agile, and in many ways better able to deal with their environment.

On the other hand, Baumeister and his colleagues also found that people with high self-esteem sometimes delude themselves. They tend to believe that they are more than likable and attractive, have ameliorate relationships, and brand ameliorate impressions on others than people with depression self-esteem. But objective measures show that these beliefs are oft distortions rather than facts. Furthermore, people with overly loftier cocky-esteem, particularly when it is accompanied by narcissism, defensiveness, conceit, and the unwillingness to critically assess one'southward potential negative qualities, take been plant to engage in a variety of negative behaviors (Baumeister, Smart, & Boden, 1996). For example, people with loftier self-esteem are more likely to be bullies (despite also being more likely to defend victims) and to experiment with booze, drugs, and sex.

Todd Heatherton and Kathleen Vohs (2000) found that when people with extremely high self-esteem were forced to fail on a difficult task in front of a partner, they responded past interim more unfriendly, rudely, and arrogantly than did those with lower cocky-esteem. And research has found that children who inflate their social self-worth—those who think that they are more popular than they really are and who thus have unrealistically high self-esteem—are besides more aggressive than children who do not show such narcissistic tendencies (Sandstrom & Herlan, 2007; Thomaes, Bushman, Stegge, & Olthof, 2008). Such findings raise the interesting possibility that programs that increase the self-esteem of children who neat and are aggressive, based on the notion that these behaviors stem from depression cocky-esteem, may practise more impairment than good (Emler, 2001). If you are thinking like a social psychologist, these findings may non surprise you—narcissists tend to focus on their self-concerns, with fiddling concern for others, and nosotros have seen many times that other-concern is a necessity for satisfactory social relations.

Furthermore, despite the many positive variables that chronicle to high self-esteem, when Baumeister and his colleagues looked at the causal function of self-esteem they found little evidence that loftier self-esteem caused these positive outcomes. For example, although loftier self-esteem is correlated with academic accomplishment, it is more the effect than the crusade of this achievement. Programs designed to boost the self-esteem of pupils have not been shown to ameliorate academic functioning, and laboratory studies have generally failed to find that manipulations of self-esteem cause improve job functioning.

Baumeister and his colleagues concluded that programs designed to boost self-esteem should be used just in a limited way and should not be the merely approach taken. Raising self-esteem will not brand immature people exercise meliorate in school, obey the law, stay out of problem, go along amend with other people, or respect the rights of others. And these programs may fifty-fifty backlash if the increased self-esteem creates narcissism or conceit. Baumeister and his colleagues suggested that attempts to boost self-esteem should only be carried out as a reward for good behavior and worthy achievements, and non but to attempt to make children feel better about themselves.

Although we naturally desire to take social status and loftier self-esteem, we cannot always promote ourselves without any regard to the accuracy of our self-characterizations. If we consistently distort our capabilities, and peculiarly if we do this over a long period of time, nosotros will merely end up fooling ourselves and perhaps engaging in behaviors that are not really beneficial to usa. About of us probably know someone who is convinced that he or she has a particular talent at a professional level, only we, and others, can see that this person is deluded (but mayhap we are too kind to say this). Some individuals who audition on television talent shows spring to listen. Such self-delusion can become problematic considering although this high self-esteem might propel people to piece of work harder, and although they may bask thinking positively about themselves, they may be setting themselves up for long-term thwarting and failure. Their pursuit of unrealistic goals may also take valuable fourth dimension abroad from finding areas they have more than chance to succeed in.

When we self-raise too much, although we may feel good near it in the short term, in the longer term the outcomes for the self may non be positive. The goal of creating and maintaining positive self-esteem (an affective goal) must be tempered past the cognitive goal of having an accurate cocky-view (Kirkpatrick & Ellis, 2001; Swann, Chang-Schneider, & Angulo, 2007). In some cases, the cognitive goal of obtaining an accurate picture of ourselves and our social world and the affective goal of gaining positive self-esteem work hand in mitt. Getting the best grade in an important exam produces authentic cognition about our skills in the domain every bit well as giving united states some positive self-esteem. In other cases, the two goals are incompatible. Doing more poorly on an examination than we had hoped produces conflicting, contradictory outcomes. The poor score provides accurate information about the self—namely, that nosotros take not mastered the bailiwick—but at the same time makes u.s.a. feel bad.Cocky-verification theory states that people ofttimes seek confirmation of their self-concept, whether it is positive or negative (Swann, 1983). This sets upwards a fascinating clash between our need to cocky-raise against our demand to be realistic in our views of ourselves. Delusion versus truth: which one wins out? The answer, of course, every bit with pretty much everything to do with human social behavior, is that it depends. Simply on what does it depend?

One cistron is who the source is of the feedback about u.s.: when we are seeking out close relationships, nosotros more than often grade them with others who verify our self-views. We likewise tend to feel more than satisfied with interactions with self-verifying partners than those who are ever positive toward us (Swann, De La Ronde, & Hixon, 1994; Swann & Pelham, 2002). Self-verification seems to be less important to us in more distant relationships, as in those cases we oftentimes tend to prefer self-enhancing feedback.

Some other related factor is the part of our cocky-concept we are seeking feedback nigh, coupled with who is providing this evaluation. Permit's say you are in a romantic relationship and you ask your partner and your close friend most how physically attractive they recall yous are. Who would you desire to requite you self-enhancing feedback? Who would you lot want more honesty from? The evidence suggests that most of u.s. would prefer self-enhancing feedback from our partner, and accuracy from our friend (Swann, Bosson, & Pelham, 2002), as perceived physical attractiveness is more fundamental to romance than friendship.

Under certain conditions, verification prevails over enhancement. Nonetheless, we should non underestimate the power of self-enhancement to oftentimes cloud our ability to exist more realistic about ourselves. For example, cocky-verification of negative aspects of our self-concept is more likely in situations where we are pretty certain of our faults (Swann & Pelham, 1988). If there is room for doubt, and then enhancement tends to rule. Besides, if nosotros are confident that the consequences of getting innaccurate, cocky-enhancing feedback about negative aspects ourselves are minimal, then we tend to welcome self-enhancement with open arms (Aronson, 1992).

Therefore, in those situations where the needs to enhance and to verify are in conflict, we must acquire to reconcile our self-concept with our self-esteem. Nosotros must exist able to accept our negative aspects and to work to overcome them. The ability to balance the cognitive and the affective features of the self helps us create realistic views of ourselves and to interpret these into more than efficient and constructive behaviors.

There is one final cautionary note most focusing too much on self-enhancement, to the detriment of self-verification, and other-business organization. Jennifer Crocker and Lora Park (2004) accept identified some other toll of our attempts to inflate our self-esteem: nosotros may spend so much time trying to enhance our cocky-esteem in the optics of others—by focusing on the clothes we are wearing, impressing others, and and so along—that nosotros have fiddling fourth dimension left to really ameliorate ourselves in more meaningful ways. In some extreme cases, people experience such strong needs to improve their self-esteem and social status that they deed in believing or ascendant ways in order to gain it. As in many other domains, and then, having positive cocky-esteem is a adept affair, but we must be careful to temper it with a good for you realism and a business organisation for others. The existent irony here is that those people who do prove more other- than self-business organization, those who engage in more prosocial behavior at personal costs to themselves, for example, often tend to take college self-esteem anyway (Leak & Leak, 2003).

- Self-esteem refers to the positive (high cocky-esteem) or negative (low self-esteem) feelings that we accept about ourselves.

- Self-esteem is adamant both by our own achievements and accomplishments and by how we think others are judging us.

- Self-esteem can exist measured using both direct and indirect measures, and both approaches detect that people tend to view themselves positively.

- Self-esteem shows important variations across different cultural, gender, and age groups.

- Considering information technology is then important to take cocky-esteem, nosotros may seek out, procedure, and remember information in a way that allows us to meet ourselves even more positively.

- High self-esteem is correlated with, simply does not cause, a variety of positive outcomes.

- Although high self-esteem does correlate with many positive outcomes in life, overly loftier cocky-esteem creates narcissism, which can lead to unfriendly, rude, and ultimately dysfunctional behaviors.

- In what ways do you attempt to boost your own cocky-esteem? Which strategies do you lot feel have been particularly effective and ineffective and why?

- Do you lot know people who have appropriately high cocky-esteem? What about people who are narcissists? How do these individual differences influence their social beliefs in positive and negative ways?

- "It is relatively like shooting fish in a barrel to succeed in life with low cocky-esteem, but very difficult to succeed without self-control, cocky-discipline, or emotional resilience in the face of setbacks" (Twenge & Campbell, 2009, p. 295). To what extent do you agree with this quote and why?

References

Aronson, E. (1992). The render of the repressed: Dissonance theory makes a comeback. Psychological Research, 3(4), 303–311.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, M. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause meliorate performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles?Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(one), ane–44.

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. K. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and assailment: The dark side of loftier self-esteem.Psychological Review, 103(i), 5–34.

Brown, J. D. (2010). Beyond the (not so) great divide: Cultural similarities in self-evaluative processes. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 318-330.

Cai, H., Brown, J. D., Deng, C., & Oakes, M. A. (2007). Self-esteem and civilization: Differences in cognitive self-evaluations or melancholia self-regard?.Asian Periodical Of Social Psychology,10(3), 162-170. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00222.x

Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. Thousand., Lavallee, L. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(i), 141-156.

Campbell, Due west., Bosson, J. Grand., Goheen, T. W., Lakey, C. E., & Kernis, Thou. H. (2007). Do narcissists dislike themselves 'deep down inside?'.Psychological Scientific discipline,18(iii), 227-229. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01880.x

Campbell, W., Bush, C., Brunell, A. B., & Shelton, J. (2005). Understanding the Social Costs of Narcissism: The Example of the Tragedy of the Commons.Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin,31(x), 1358-1368. doi:10.1177/0146167205274855

Campbell, W. G., & Foster, C. A. (2002). Narcissism and commitment in romantic relationships: An investment model analysis.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 484–495.

Campbell, West. K., Rudich, E., & Sedikides, C. (2002). Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 358–368.

Carlson, E. N., Vazire, South., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2011). You probably call up this newspaper's almost you: Narcissists' perceptions of their personality and reputation.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 185–201.

Crocker, J., & Park, 50. Eastward. (2004). The plush pursuit of self-esteem.Psychological Bulletin, 130, 392–414.

Emler, Due north. (2001). Self esteem: The costs and causes of low self worth. York: York Publishing Services.

Greenwald, A. M., & Farnham, S. D. (2000). Using the Implicit Association Examination to measure self-esteem and self-concept.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(vi), 1022–1038.

Heatherton, T. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2000). Interpersonal evaluations following threats to self: Role of self-esteem.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 725–736.

Heine, Due south. J. (2004). Positive cocky-views: Agreement universals and variability.Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology,2, 109-122.

Heine, S. J., & Lehman, D. R. (1999). Civilisation, self-discrepancies, and self-satisfaction.Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin,25(eight), 915-925. doi:x.1177/01461672992511001

Heine, Due south. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is at that place a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review, 106(four), 766-794. doi: ten.1037/0033-295X.106.iv.766

Held, B. S., (2002) The tyranny of the positive attitude in America: Observation and speculation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 965-992. doi: x.1002/jclp.10093

Helgeson, V. Southward., & Mickelson, K. (2000). Coping with chronic disease among the elderly: Maintaining self-esteem. In S. B. Manuck, R. Jennings, B. S. Rabin, & A. Baum (Eds.),Behavior, health, and crumbling.Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hepper, East. G., Gramzow, R. H., & Sedikides, C. (2010). Individual differences in cocky-enhancement and self-protection strategies: An integrative assay.Journal Of Personality,78(2), 781-814. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00633.x

John, O. P., & Robins, R. W. (1994). Accuracy and bias in cocky-perception: Individual differences in self-enhancement and the function of narcissism.Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology,66(1), 206-219. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.ane.206

Kirkpatick, L. A., & Ellis, B. J. (2001). Evolutionary perspectives on cocky-evaluation and self-esteem. In M. Clark & One thousand. Fletcher (Eds.),The Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology, Vol. 2: Interpersonal processes (pp. 411–436). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Kling, K. C., Hyde, J., Showers, C. J., & Buswell, B. North. (1999). Gender differences in self-esteem: A meta-assay.Psychological Bulletin,125(4), 470-500. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.iv.470

Kwan, V. Y., John, O. P., Kenny, D. A., Bond, M. H., & Robins, R. West. (2004). Reconceptualizing individual differences in cocky-enhancement bias: An interpersonal approach.Psychological Review,111(1), 94-110. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.94

Leak, Grand. K., & Leak, Thou. C. (2003). Adlerian Social Involvement and Positive Psychology: A Conceptual and Empirical Integration.The Journal of Private Psychology, 62(3), 207-223.

Mead, G. H. (1934).Listen, Cocky, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Robins, R. Due west., Trzesniewski, K. H., Tracy, J. L., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2002). Global self-esteem beyond the life bridge.Psychology and Crumbling, 17,423-434.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the boyish self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press.

Rothermund, K., & Brandtstadter, J. (2003). Coping with deficits and loss in later life: From compensatory action to accommodation.Psychology and Crumbling, 18,896-905.

Ryff, C. D. (1991). Possible selves in adulthood and old age: A tale of shifting horizons.Psychology and Aging, 6,286-295.

Sandstrom, M. J., & Herlan, R. D. (2007). Threatened egotism or confirmed inadequacy? How children's perceptions of social condition influence aggressive behavior toward peers.Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(2), 240–267.

Sanitioso, R., Kunda, Z., & Fong, K. T. (1990). Motivated recruitment of autobiographical memories.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(ii), 229–241.

Schlenker, B. R. (2003). Self-presentation. In M. R. Leary, J. P. Tangney, K. R. E. Leary, & J. P. Due east. Tangney (Eds.),Handbook of self and identity (pp. 492–518). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Sprecher, Southward., Brooks, J. E., & Avogo, Westward. (2013). Cocky-esteem among young adults: Differences and similarities based on gender, race, and cohort (1990–2012).Sex Roles,69(v-half-dozen), 264-275.

Swann, W. B., Jr. (1983). Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the cocky. In J. Suls & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 2, pp. 33–66), Hillsdale, NJ: Erlba

Swann, W. B., Bosson, J. K., & Pelham, B. Westward. (2002). Different partners, different selves: Strategic verification of circumscribed identities.Personality And Social Psychology Message,28(9), 1215-1228. doi:10.1177/01461672022812007

Swann, Westward. B., Jr., Chang-Schneider, C., & Angulo, S. (2007). Cocky-verification in relationships as an adaptive process. In J. Wood, A. Tesser, & J. Holmes (Eds.),Self and relationships. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Swann, W. B., Jr., De La Ronde, C., & Hixon, J. One thousand. (1994). Authenticity and positivity strivings in marriage and courting.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 857–869.

Swann, W. B., Jr., & Pelham, B. W. (2002). Who wants out when the going gets skilful? Psychological investment and preference for self-verifying college roommates.Journal of Self and Identity, 1, 219–233.

Tafarodi, R. W., & Swann, Due west. B., Jr. (1995). Self-liking and self-competence equally dimensions of global self-esteem: Initial validation of a mensurate.Journal of Personality Cess, 65(ii), 322–342.

Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., Stegge, H., & Olthof, T. (2008). Trumping shame by blasts of noise: Narcissism, self-esteem, shame, and aggression in young adolescents.Child Development, 79(6), 1792–1801.

Tobin, Vanman, Verreynne, & Saeri, A. K. (2014). Threats to belonging on Facebook: Lurking and ostracism. Social Influence. doi:x.1080/15534510.2014.893924

Twenge J. (2011). Narcissism and culture.The handbook of narcissism and egotistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments [due east-book]. Hoboken, NJ Us: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Twenge, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2009).The narcissism epidemic.New York, NY: Gratuitous Press.

Twenge, J. 1000., Konrath, S., Foster, J. D., Campbell, W., & Bushman, B. J. (2008). Egos inflating over time: A cantankerous-temporal meta-analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory.Journal Of Personality,76(iv), 875-902. doi:x.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00507.10

Yamaguchi, Southward., Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., Murakami, F., Chen, D., Shiomura, 1000., & … Krendl, A. (2007). Apparent universality of positive implicit self-esteem.Psychological Science,18(vi), 498-500. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01928.10

Which Of The Following Behaviors Would A Person With Low Self-control Not Be Likely To Exhibit?,

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/chapter/the-feeling-self-self-esteem/

Posted by: boosthatrepasis65.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Of The Following Behaviors Would A Person With Low Self-control Not Be Likely To Exhibit?"

Post a Comment